The Secret History

1992, Donna Tartt

1992, Donna Tartt

“Does such a thing as 'the fatal flaw' that showy dark crack running down the middle of a life, exist outside literature? ... Now I think it does. And I think that mine is this: a morbid longing for the picturesque at all costs.”

I would recommend this book to:

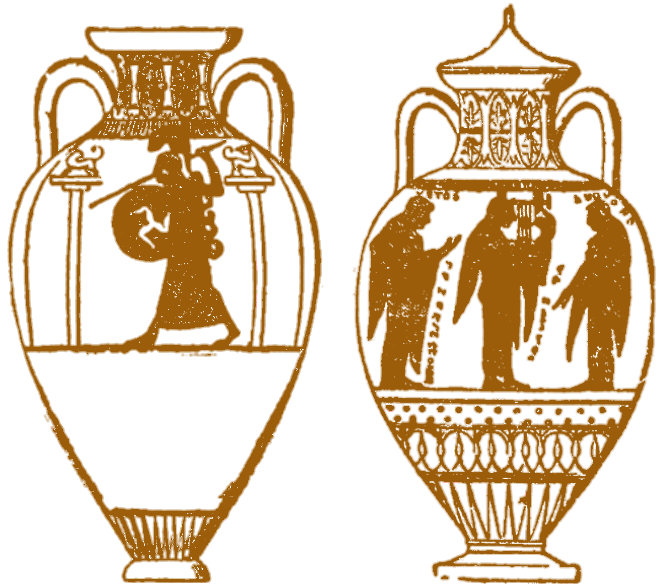

I enjoyed this book so much, it inspired me to study Ancient Greek. It’s the perfect balance of philosophy and entertainment; a warning about the idealism and detachment of wealthy intellectuals as well as a murder mystery and tragedy.  In it, Richard Papen seeks to escape the boredom of suburban life by studying Ancient Greek at a New England college; he’s obsessed with the mysterious and picturesque, and tries to remodel his life to fit in with a group of wealthy, erudite students who seem to be living his dream life. However, as they pursue Greek divine madness, their deep internal flaws are gradually revealed, and he’s coerced into committing crimes and his life becomes a mess, leaving him wishing he was content with things before.

In it, Richard Papen seeks to escape the boredom of suburban life by studying Ancient Greek at a New England college; he’s obsessed with the mysterious and picturesque, and tries to remodel his life to fit in with a group of wealthy, erudite students who seem to be living his dream life. However, as they pursue Greek divine madness, their deep internal flaws are gradually revealed, and he’s coerced into committing crimes and his life becomes a mess, leaving him wishing he was content with things before.

The book doesn’t teach a lesson as much as satirizes and warns. There is no happy ending for the characters, meaning it wasn’t written to give advice, but to project the deeply personal struggles of Tartt and her colleagues into a fictional story. I’m not saying they murdered someone, but the characters’ motives and flaws — their pretentiousness, detachment, self-destructiveness, and yearning to escape modern life were things she described so well, she probably felt or saw them herself. But she doesn’t offer fulfilling alternative solutions to these problems (Richard couldn’t bear the ennui of California, and the hospitalized Henry had nothing to do but read endlessly),  only the consequences of their reactions to them.

only the consequences of their reactions to them.

While the book can be enjoyed by everybody, I’d especially recommend it to people studying the humanities; it was written by one of such people, for such people, and has lots of allusions just for us. Rather than only giving cliché shows of characters’ intelligence, like reading War and Peace or Aristotle, she references what impresses only us — like Proust, John Donne, or lines from Crime and Punishment. In scenes where languages are being translated she references inflections, “cheating” in translation, Ancient Greek cases, and so on.

One literary influence which was very interesting was that of Euripides, who describes the beauty and danger of divine madness, the spiritual state induced trying to summon the gods. Divine madness is also central to the tragedies of Tartt’s book, and its hallucinations, like rivers of honey, are taken from his play. But while Euripides lived in a time when divine mania and belief in Greek gods were common, her characters take the perspectives of those stifled by the ennui and predictability of modern life, which makes it a lot more relatable.

“And what could be more … beautiful, to souls like the Greeks or our own, than to lose control completely? To throw off the chains of being for an instant, to shatter the accident of our mortal selves? If we are strong enough in our souls we can rip away the veil and look that naked, terrible beauty right in the face; let God consume us, devour us, unstring our bones. Then spit us out reborn.”

I like that the prose is affected by the narrator’s experiences as a modern person who reads old books — slightly antiquated, with French phrases and modern colloquialisms thrown in. His obsession with the beautiful also results in captivating, vibrant descriptions of the world around him; it combines traditional figurative language with modern pacing, resulting in the richness of classic literature without being dragged down by its usual stuffy, ornate diction. You could say it has the best of both literary worlds.

I dislike little about the book except that the use of suspense felt somewhat cheap at times. In its latter half, she excessively relies on cliffhangers to retain interest. Also, Charles and Camilla seemed somewhat flat compared to the others; true, they weren’t important characters, but it lessens the book’s sense of reality. For example, Richard’s apparently closest to Charles, but he’s rarely depicted hanging out with him or learning about his life. But these are all minor flaws.

Back

Written June 21, 2025.