Notes from Underground

1864, Fyodor Dostoyevsky

I'd recommend this book to:

- Anyone who feels they have a very severe problem with thinking too much

- Those whom enjoy more morbid literature

- People who like Dostoyevsky for his characters' complex inner workings

- People looking for shorter classics (it's about one hundred pages.)

People's enjoyment of this book seems to be a flip of a coin. Some people regard the narrator as nothing but a raving madman*, while others see in him an uncanny resemblance of themselves. Personally, I'm one of the latter sort ... O.K., perhaps it's slightly troubling that I relate to a “raving madman”, but anyway, I enjoyed this enough to write a review.

Contents

This book is divided into two sections: the first discussing the author's thoughts and ideas, the second his social life in his younger years.

In the first section, he introduces himself as a “sick and spiteful man”—suffering and unhealthy, but too spiteful to do anything about it. He deliberately avoids all that is reasonable and healthy—finding a better apartment, treating his illness, acting within common sense, all out of “spite”. Spite for taking the conventional, predictable road, for being some kind of healthy, happy worker-bee with no individuality.

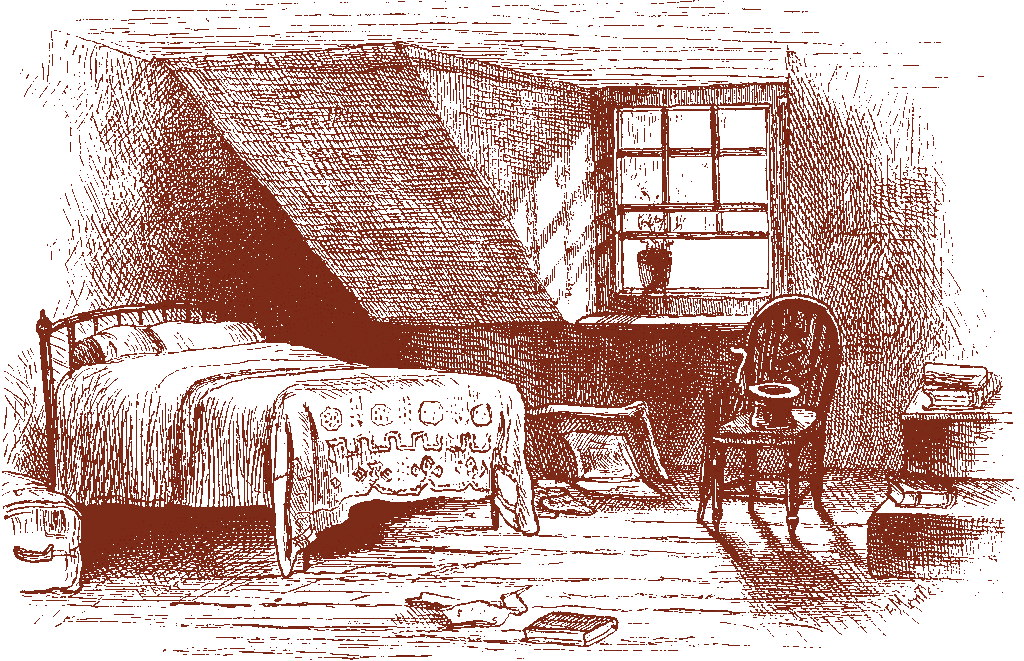

Generally, he spends so much time thinking and opining that he can't bring himself to actually do anything with his life—a sort of mentally imposed paralysis. So he rots in his apartment alone, thinking and thinking, tormenting himself with thoughts and memories.

These deep, unhealthy mental recesses still hold a good reflection of the erratic, irrational core of human nature. Dostoyevsky understands that humanity is guided on by desires that logic can't always explain, and that we sometimes know things are harmful to us, but we do them anyway to satisfy irrational whims. That humanity is proud, fickle, and restless, that even if we have everything we “need” to “guarantee” us happiness and health, we can still turn to rebelliousness and destruction. (In contrast, I have read books that argued that people are mainly products of their circumstances who would become “good” and reasonable if they were simply taught, shown the way.) One of the major things he notes about humanity is that we don't necessarily want safety and calculated guarantees as much as we want life, risk, adventure, and individuality. Other themes are discussed, such as technology, the nature of goals, and the uselessness of extensive thinking.

Not only in ideologies is he complex, however, but in his character as well, for his heart and mind lead him in two different directions. His mind is proud, cunning, and revels in depravity, but his heart is guilty and self-hating, and yearns to be kind and honest. And no matter how much he tries to stifle his heart with his mind, he can't. It's interesting to watch.

So sometimes this book expresses very serious, complex ideas to be taken apart and analyzed, but other times, the main character is just a classic Dostoyevskian edgelord—an unhealthy, sickly, pathetic little scrap, so far gone it's comical. At the core, there's an idea perhaps relatable to reality, but it is so extreme and exaggerated in the character you can't help but laugh. In the second part of the book, his proud, self-contradictory, obsessive mind is applied to reality, in which he embarrasses himself over and over... severely. Maybe it's mean of me to say, but the narrator even seemed to put in effort to embarrass himself.

Anyhow, this last part was probably my favorite:

Should one be content with a dull but real world, or feed off vibrant but fleeting dreams? This is more relevant than ever in our age of Internet and social media, when “everything is at our fingertips”. Moreover, it's perhaps an explanation for why Dostoyevsky's writing style often seems “plain”—he doesn't want to romanticize anything, to make anything more vivid, cozy, and poetic than reality, he wants to portray life and humanity for what they are.

*Most notably, Vladimir Nabokov once wrote a lengthy review attacking Dostoyevsky, saying among other things that his characters were all lunatics.

Page created March 11, 2024. Last updated March 22, 2024