Languages I am learning

Here are some of the languages I am learning or shall learn.

German (A2)

I’d like to read German literature and visit Germany someday. Besides, I associate it with fond memories of my old school. My German class’ teacher grew up in Germany, and she’d tell this young American audience all about the country — how they had a shopping street called Der Zeil, were blunt but loyal friends, earned money for recycling, ate white asparagus, made politically satirical parade floats for Karneval, and so on.

Experience

German grammar is relatively easy — at least, as an English speaker. The most difficult part of the language is probably the adjectives, which have three declensions. Memorizing the words’ genders (which are largely random) is tedious, but that’s all.Grammar

Latin (B1)

I’d like to read Roman literature — Virgil, Juvenal, the works. I also find the sound and grammar beautiful.

Experience

As with other Romance languages, Latin’s verb system is complex. Five conjunctions, six tenses, a subjunctive, an active and passive voice; not to mention participles, gerunds, special tense rules with sensory verbs, and so on. This is the most time-consuming part of Latin, and it’s easy to confuse all the rules after learning so many. There are six cases for nouns; they’re pretty easy once you’ve memorized them, except for the third declension, whose nouns have a lot of weird stems. Memorizing five declensions sounds hard, but the fourth and fifth are very rare.

Classic literature in any language uses advanced grammar, but I can say that the hardest Latin poetry is substantially more complicated than the hardest English and Russian poems I know. Russian poets will mess with word order a little, but there are Latin poets whose writing is a syntactic wordsalad, only understood with a very solid grasp of grammar and literary techniques.Grammar

Latin is beautiful, but largely useless. The only real reason to learn it is to read poems and plays by a handful of people who have been dead for hundreds or thousands of years. Some people also say they learn Latin to help them study law, medicine, or English etymology, which I personally don’t consider a strong reason for torturing yourself with subjunctive inflections or the passive periphrastic. There are also very few websites, YouTube channels, music, or modern books in Latin.

That being said, the few things that are readable in Latin are some of the most beautiful things I've ever read, especially Virgil, who is an absolute genius. There are few languages where translations and original texts contrast as much as in Latin, whose words are like rich, gilded honey compared to the stiff hardtack of English. Sometimes I read Latin poetry without even knowing what it means -- Catullus 16, for example -- simply to appreciate the dulcet sound.

Yields

Russian (B1)

Almost all of my interests align with the strong suits of Russian culture – literature, classical music, art, ice-skating, ballet, and physics. I also happen to think Russian is the most beautiful language. I like the Slavic languages generally, but unlike the other ones, Russian’s spoken by many people.

Experience

The verbs are and always will be deeply annoying. There's a pattern to it, but the pattern is so complex that to fully grasp it, you'll need to spend years developing instincts for it. In the meantime, all you can do is memorize the general rules.

Russian websites online will say, "it’s easy! You replace verbs' "-ать/ить" suffixes with "-ю, ишь"". They’re simplifying the language as to not intimidate foreigners, but I'll tell you the ugly truth. These rules don’t cover the immense multitude of verbs that end with other things: влечь, перевести, мыть, and so on. As somebody who’s reading Russian literature in the original, I memorized Zaliznyak’s sixteen-declension system, and whenever I’m learning a new verb, I look it up on Wiktionary, which uses this system. Others will call me a madman for my efforts, but I swear by my method.

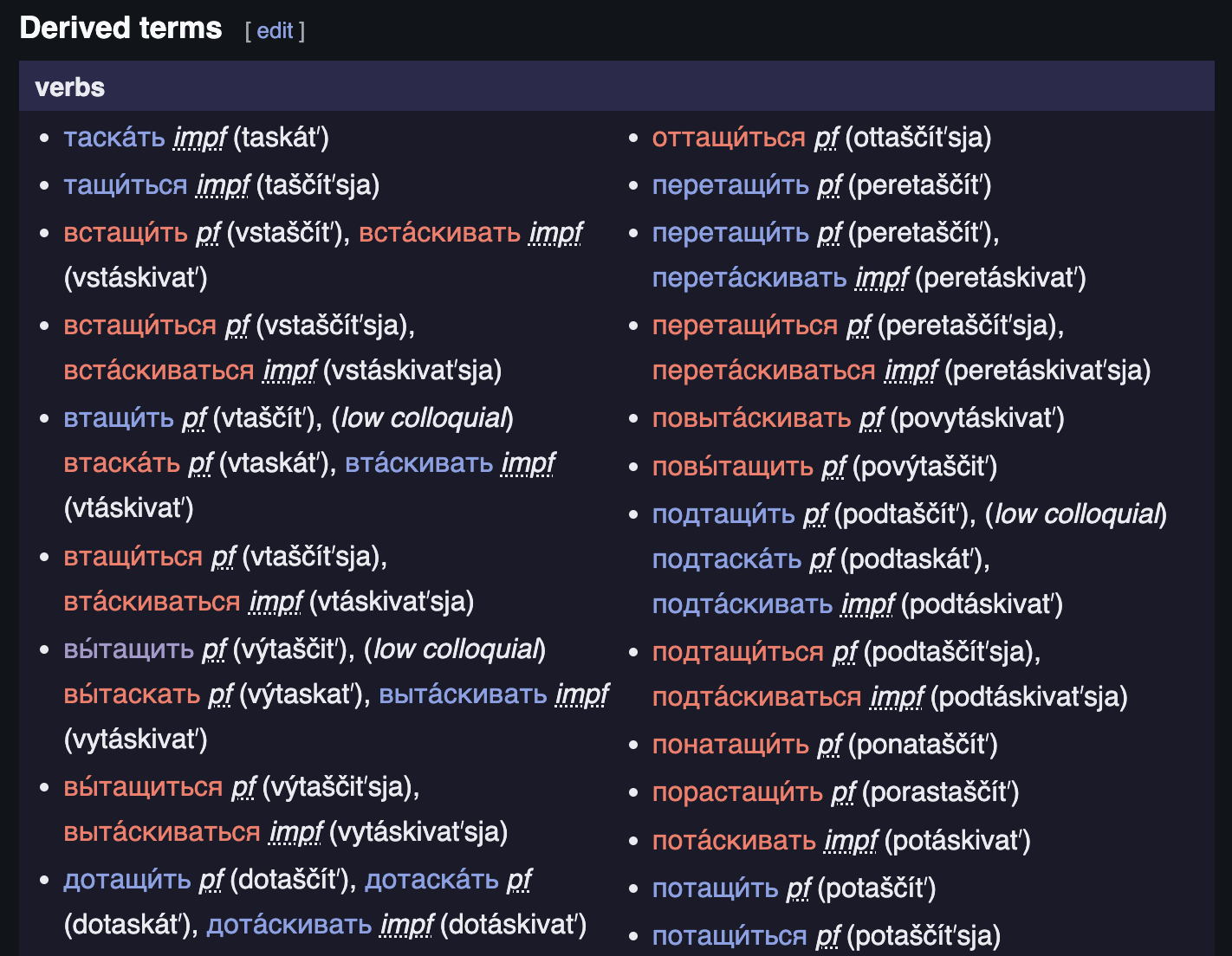

Endings aren’t the only difficulty :) every verb has two forms: imperfective and perfective. And then there are verbs' "derived forms" (see right.) You know how in English, we have words with the same stems and different prefixes, like "compose", "propose", "transpose"? Russian experiences this, but to an extreme extent -- it's confusing to memorize.

There are some other challenges — when discussing dates and times in Russian, there are numerous tedious preposition rules. Russian words are also quite long.

Grammar

It is an abundant language in terms of resources. There are tons of YouTube channels and Quizlet/Anki decks you can use and large social media platforms exclusively using the language. Its yields are very rich, too. Many people (deservingly) extol Russian literature, but their cinema and rock music are also amazing. Even if you never meet Russian speakers, it may help you understand Serbian, Ukrainian, Polish, and so on (though learning Interslavic is better for that purpose.)

I have heard stories online of people recieving comments about “supporting imperialism/the war” when they say they’re learning Russian. In my experience, though, pretty much everyone offline is normal about it. If anything, though, learning Russian may help in antiwar efforts — I know Ukrainian refugees that don’t speak a speck of English and need stuff translated into Russian, and if anything, I regret not learning the language earlier to help them. They must be very confused and lonely.

Yields

Ancient Greek (A1)

Just as with the other languages, I am learning this one to read, like a nerd; I find Greek philosophy and Hellenic paganism interesting. Finally, I just want another language with an alphabet my compatriots cannot put in Google Translate, so I can use it to write whatever I’d like.

Experience

Of all the languages I've ever learned, this one is probably the most painful. The verbs are overwhelmingly complex. There are six tenses, three voices, a subjunctive, an optative, and each verb has six principal parts.

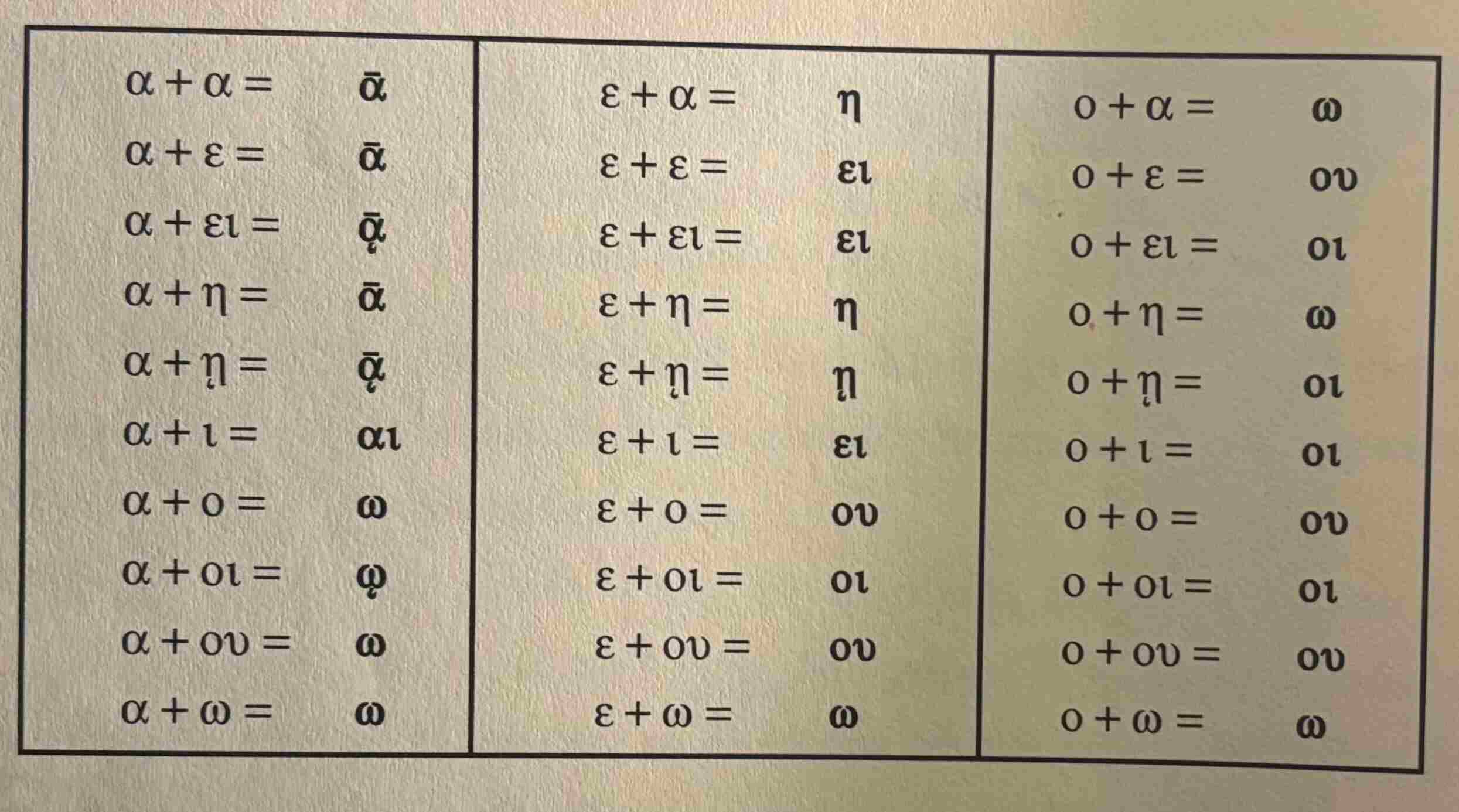

Ancient Greek in particular is quite picky about pronunciation. It's a pitch language, like Chinese, meaning there are set rules about the pitch of every syllable in a word. There are numerous rules and exceptions to rules about pitches, and that's not even mentioning the difficulty of "euphony", the Greek concept of blending letters together so they sound smoothly (see right for an example.)

There is then the issue of Greek vocabulary. If you learn languages that are part of the same family, or which influenced each other -- English and German, for example, it's easy because some words sound similar. However, unless you know Modern Greek, Ancient Greek will sound unlike any language you've ever known. There are also several dialects of Ancient Greek, and you'll have to learn all of them to have full access to Greek literature.I could go on and on about how tough this language is -- the syntax is confusing, memorizing vowel lengths is confusing, there are virtually no resources for study. Suffice to say it's just a bloodbath of a language -- I don't know if I love or hate it more.Grammar

There isn’t much you can do with the language besides reading poems and plays. At least Latin was popular as a scientific language -- Greek’s only used for abstruse terms like “oligosaccharide.” If nothing else, it’s a cool party trick, I guess. I write Ancient Greek blessings and curses on my school’s whiteboards because it’s funny.

Yields

Vietnamese (Heritage speaker)

As a Vietnamese-American, I dine, shop, celebrate holidays, and generally hang out in places where people expect me to speak the language. It’s almost shameful when I cannot, and even more so that I can speak a bunch of Western languages better.

Polish (Not started)

Its reputation as a brutal language with crazy orthography only makes me more excited, the same way the danger of Mount Everest only excites some people.

Old Slavonic (Not started)

I've come to realize that languages bring me a joy that almost nothing else does. I like dead languages because they're literary and there's no embarrassment from native speakers -- the environment is just you and a bunch of other nerds reading thousand-year-old texts, and if someone makes a mistake, it's totally acceptable. I like Slavic languages a lot, maybe because I've grown blasé to more popular languages like Italian or French.

Page created April 13, 2024.